Making System-Level Claims from a Flawed Methodology: A Response to the ERO Report

In response to the Education Review Office (ERO) report on the preparedness of new teachers, the New Zealand Council of Deans of Education has expressed their concern that “the report’s findings are based on a flawed methodology and should not inform any proposed system-wide changes”. What does it mean to say that this report had a flawed methodology? We identify two key issues.

Recruitment and participants

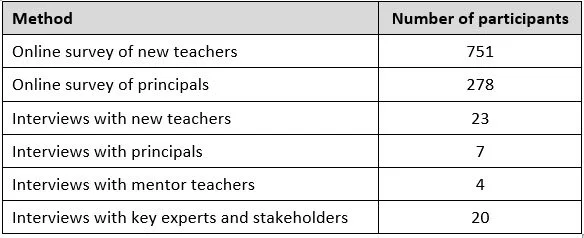

The first issue relates to how the participants for the research were found. The ERO report drew on data from the following participants:

Invitations to take part in the survey were emailed to all Provisionally Certified Teachers (PCTs), who then chose whether or not to respond to the survey. New teachers could then volunteer through the survey to take part in interviews. No numbers were provided for the total population of PCTs. Principals were emailed a survey invitation, and could also choose whether or not to take part. No information was provided about how many principals were approached, nor whether an invitation was sent to all principals in Aotearoa New Zealand. As the ERO report states, this is “self-selection sampling” (p. 126). It is not possible to make any claims to representativeness without knowing more about the numbers involved, or how those numbers compare to the demographics of the wider population.

The principals who were interviewed were “selected through the Secondary Principals’ Association of New Zealand (SPANZ) and Teaching Council recommendations” (p. 125). The mentor teachers were “selected through recommendations from Teaching Council and a Mentoring PLD provider” (p. 125). No further information was provided on how the key experts and stakeholders were approached to take part in interviews. One might conclude from these statements that the principal and mentor teacher participants were known to the researchers in some capacity and were selected for the views they would convey in interviews. No information was given that would refute this understanding.

The survey and interview participants in the research conducted by ERO were a purposive sample of new teachers and related education experts. This is a commonly used sampling method for qualitative research; however, and critically, it cannot lead to generalisations about the wider population. The participants are not representative of new teachers or the personnel who support their induction into the teaching workforce.

Presentation of findings

The second key issue relates to the way the findings were reported. One part of this issue is around the language being used, which shifts meanings in subtle yet significant ways. The other part is that the report provides percentages, but never gives the number out of which these percentages were calculated, making it challenging to ascertain the significance of what is being reported.

An example to highlight these issues relates to ‘preparedness’. New teachers were asked: “Thinking back to your first term of teaching, how prepared did you feel overall for the role?” (p. 134) – a key finding being: “Nearly half (49 percent) of new teachers report being unprepared when starting their first term of teaching” (p. 44). The survey did not ask whether new teachers were prepared; rather whether they felt prepared. The language here is not equivalent.

Regarding the reporting of numbers and percentages, there are many examples to draw from. One example states:

In their first term, over a quarter of primary school new teachers feel prepared (27 percent). Over half of primary school new teachers report being unprepared overall (52 percent). More secondary school new teachers report being prepared (32 percent), and less than half feel unprepared (46 percent). (p. 50)

However, what were the frequency counts involved? How many primary teachers and how many secondary teachers responded to the survey? ERO does not make this clear. It is also not clear why these percentages do not add up to 100%. Did the remaining respondents record a neutral response?

There is a rare example of frequency counts being reported: “Only nine new teachers in our sample completed an employment-based qualification. … Of these, seven report being prepared to teach overall” (p. 65). However, it could equally be said that two of the new teachers (or 22%) who completed an employment-based qualification felt they were not prepared. These are very small numbers on which to base any kind of significant conclusion.

Educational research is needed in New Zealand to support policy development, ITE, teachers, and students. However, that research needs to be methodologically strong and rigorous, with findings and conclusions reported in an objective way that is supported by clear evidence. It is disingenuous of ERO to make sweeping claims about all new teachers in Aotearoa based on the views of a non-representative sample of participants. Additionally, it is clear that this report espouses a particular narrative. Presenting findings in a biased manner to support that narrative calls the integrity of the research into question and risks misleading readers. Education stakeholders deserve better.

Bios:

Philippa Butler is a Senior Lecturer in Research Methods. She has over 20 years’ experience conducting externally funded research projects for organisations such as the Ministry of Education, the Teaching Council, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

Jared Carpendale is a Senior Lecturer in Teacher Education. He is an experienced teacher, teacher educator, and educational researcher. He has worked on several research projects with national and international education stakeholders.